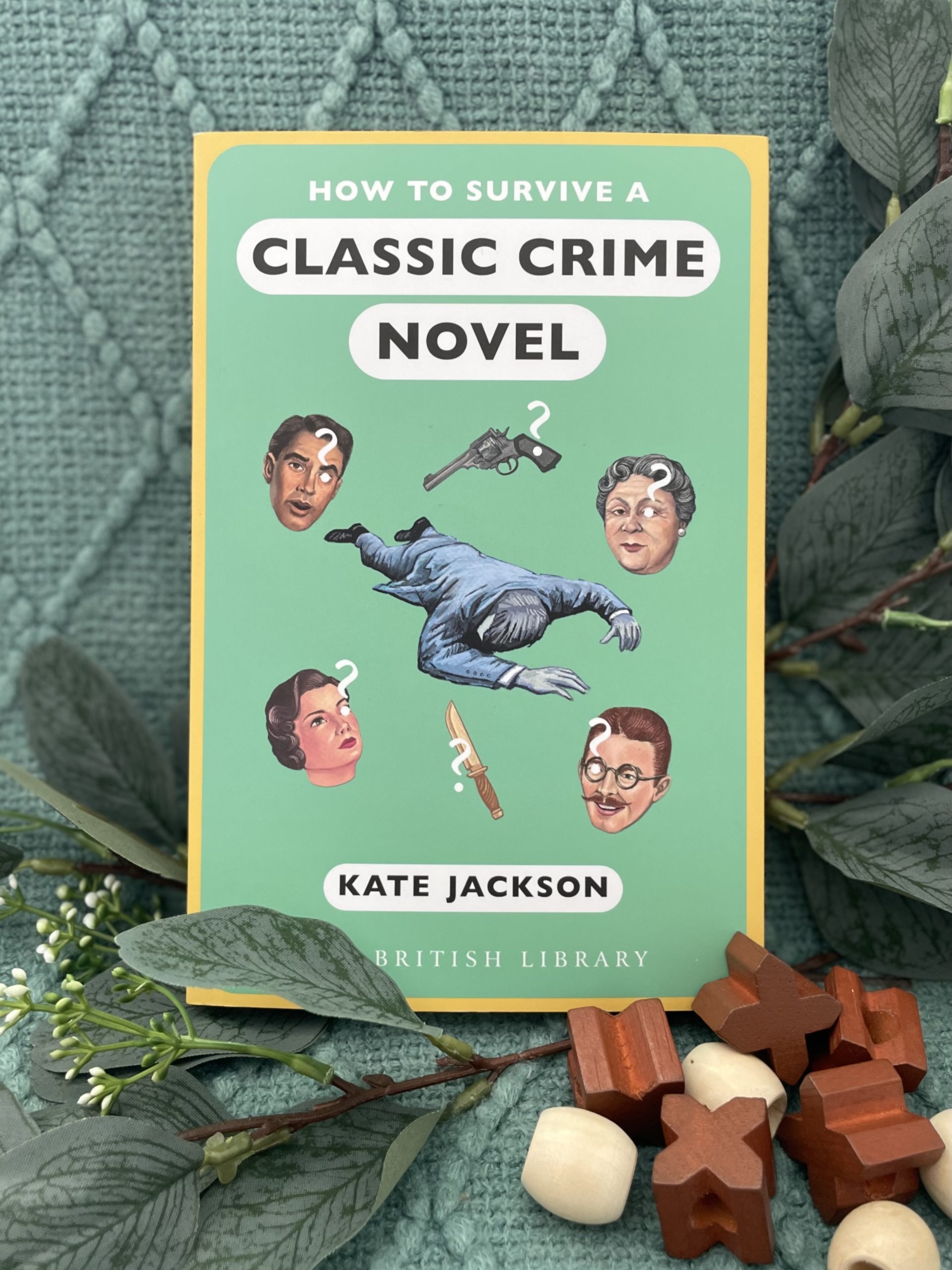

I recently came across two explorations of the crime genre that happened to intersect at an interesting time. The first: Kate Jackson (of crossexaminingcrime.com)’s wonderfully funny new release How to Survive a Classic Crime Novel. (Thanks to In Search of the Classic Mystery Novel for this find!) And second, an episode of Revisionist History by Malcolm Gladwell, exploring a taxonomy of the crime story.

These are two Very Different takes, albeit both written with a clear love for the genre. Kate Jackson writes a how-to guide, a detailed and comprehensive breakdown of tropes and variants thereof in mystery writing. Gladwell, in contrast, takes a more top-down approach, expanding a initial structure to draw conclusions about crime literature and society. Yet both serve as an interesting mirror for this crime fiction aficionado: what does it mean that I love this genre so much?

Jackson’s caricature

Let’s start with Jackson’s deconstruction of crime tropes, How to Survive a Classic Crime Novel. Jackson structures it as a how-to guide for someone trying to get through the day in a fictional crime universe. The guide breaks up life into six settings (home, commute, at a party, etc.)and adds the discovery of a corpse. Each section contains an incredibly detailed set of references and citations, disguised as how-to tips, covering different modes of murder. Before we go further – if you love Golden Age books, this is a must-read! I laughed a ton, and walked away with a hefty reading list.

In my experience, how-to guides like this tend to force me to see the genre in a new light. How to Survive a Classic Crime Novel forced me to ponder the brand variance in murderous methods. It’s hard to read a laundry list of “safety tips” without reacting impatiently to some of them. React to enough, and if you’re like me you’ll start thinking through the patterns. What do these methods say about society in the Golden Age? What makes a crime story timeless?

Take, for example, the difference between my reactions to “Agatha Christie’s Poison Checklist”, “Gift of Death”, and “The Swimming Pool”. The first: pretty funny, and also I haven’t heard of anyone dying by deliberate poison in ages. The second: did people really just get unexpected parcels in the mail? What a wild time. And the third: yep, pools as “corpse magnets” has definitely stuck around.

Note that these are all definitely classic crime tropes! No issues with the pointers or the research. I just find it interesting to see how society has evolved and changed. Presumably many of these story beats felt somewhat reasonable, yet now feel wild to consider. For me, this read reflected a couple of evolutions:

- Decreased openness. Perhaps because of crime reporting, I cannot imagine people getting such access to others’ homes or environments. The most complex of these tropes require a level of casual access to others’ homes that seem seems impossible today.

- Shifting conspiracies. The most complex plots in Golden Age mystery are still often deeply personal. Instead of modern spy and government plots, the complexity lies planning an intricate, personal murder. Maybe I’m just imagining (or reading the wrong stuff), but modern fictional murderers seem to put more effort into the cover-up, not the upfront crime…

- Class and perspective. Imagine writing a story about a house with a study and a library today, or including the galas described in the Golden Age. Mystery novels have shifted from centering the upper class and/or fabulously wealthy to the more mundane.

And yet, despite all those changes, I still love a classic crime novel. Even if mechanics feel out of time, the human stories don’t. There’s this natural tension between the mechanics of these stories and the warnings they convey. While gas ovens may no longer be so dangerous, greed and envy are just as worth watching out for. And, on the positive side, perseverance and intelligence are just as important for tackling human problems as ever.

Gladwell’s compass

Shortly after finishing How to Survive a Classic Crime Novel, I came across “Taxonomy of the Modern Mystery Story”, an episode of Malcom Gladwell’s podcast Revisionist History. In this episode, Gladwell sets up a taxonomy of crime stories, setting up two axes of analysis. The first axis explores the presence of the police (Westerns, for utter lawlessness, vs. Easterns, for pure police efficiency). The second explores police incompetence (Northerns, for simply incompetent police, vs. Southerns, for actively malicious forces).

Gladwell argues that our canon of crime stories forces us to think in these tropes, ignoring the real nature of policing. He argues that crime stories, as told, center the investigator and entitle him or her to power and influence. And he argues that these stories force us to lose the nuance in understanding real police work, at our own expense.

And – perhaps. I can understand the argument that stories make up the “cultural raw material for the way we make sense of the world.” Certainly, if you stick to only one genre or flavor of crime story, you might end up with a skewed perspective; doubly so if you excise the news from your reading diet. But for those who ingest a more varied set, surely they step back to ponder why these vastly different stories resonate.

Not only that – as evidenced by Jackson’s book, we know that mystery stories evolve to reflect their times. The fears and concerns of one group of writers (death by gas radiator or complex poisoning scheme) seem completely impossible to another. Modern mysteries increasingly center diverse voices and writers, who tell more complex and nuanced tales of law enforcement. This pops up not just in The Great Fiction – even recent cozy mysteries I’ve read acknowledge the difficulties of police work while still centering amateur detection. More modern mysteries frequently involves partnerships with police forces, or a recognition that a few bad apples makes for a complex bushel. The genre is evolving, recognizing new stories and forcing us to integrate them.

Crime and critical thinking

In a way, mystery stories are their own antidote. Solving a mystery requires critical thinking, a willingness to look beyond the surface. The best and most compelling detectives use empathy to understand their suspects, and logic to puzzle out the truth. Applying that same logic to our own world and our own lives is hard work, but so worth it.

In my non-blogger life, I’m somewhere on the spectrum. For someone who always struggled to understand others, mysteries (and stories more broadly) have always served as a roadmap. Since I was small, I’ve devoured as many stories as I can, from fantasies to advice columns, just trying to understand the world around me. And mysteries serve as a beacon in that effort, a reminder that with enough patience and logic and empathy, problems can be faced. Not only that – because mysteries can feel so timeless, historical mysteries can serve as a window into the past, a way to connect more closely with prior generations. The tropes are familiar, so I can marinate in what’s different – about characters and their roles in society and their reactions to provocation. It’s just – a little less overwhelming to process, I suppose.

Mysteries are a cultural processing mechanism, a way to decide who gets to partake in the mechanisms of justice. Not for nothing is Batman the World’s Greatest Detective – these are stories of how we process hurt and respond to it. Across all of Jackson’s tropes, and all of Gladwell’s directions, these stories share an underlying North Star: the truth. And if a dominant segment of the story-ingesting market still values that truth – both finding it and acting on it – because of these mysteries, that feels like a story worth celebrating.

Fall is soon upon us, which is (in my opinion) prime mystery season. Nothing better than a sweater and a warm mug of tea with your mystery. So expect to see more in the mystery vein from me soon! What are your favorite crime meta analyses – what should I be reading?

—

Until next time – stay cozy, and stay curious!