Have you ever seen a piece of art get so hyped up that you avoid it, because you’re worried that there’s no way it can live up to it? This is how I felt about Piranesi by Susanna Clarke, a weird and wonderful novel that unfolds via journal entries. Despite seemingly everyone in the entire world raving about this novel in 2020, it’s taken me till now to work up the courage to read it. And I’m glad I finally took the plunge, because it’s a work of epistolary art.

A novel for its time

Piranesi comprises a series of journal entries from the titular protagonist, who lives in an expansive house that floods on a regular basis. He is aware of only one other living human, the Other, who visits him twice a week to search for the Great Knowledge. Piranesi views the Other as a friend – one who gives him critical supplies and provides much-needed company. But his world turns upside down when the Other warns him off a potential new visitor, called 16, who poses a threat to his way of life.

Many other reviewers have covered elements of what make Piranesi great. The magical writing; the atmospheric setting; the thematic complexity. Is this a book about isolation? About identity? An allegory for reading? All of the above? It helped, also, that the book landed mid-pandemic, as we were all losing our minds in isolation. Suddenly, the protagonist’s plight – stuck in a big house, nobody to speak with, no way to get out – became all the more relatable. Reviews consistently return to the narrator as a standout – his innocent voice and his selflessness were the balm we all needed in 2020.

But I am reading this two years later, when I’m allowed out of my house. The narration brings back memories of those times, and makes me glad we’ve left them behind. The memory of the Isolation Times actually increased the horror I felt at Piranesi’s situation – it’s entirely possible this would not have stuck out quite as much pre-pandemic. It’s a weird coincidence of publish date – after all, book schedules are set well in advance. It makes me wonder how many other Situational Novels I won’t be able to fully understand – and how future generations will interpret this one.

The dramatic irony of journals

(This section contains mild spoilers for Piranesi. Be warned!)

Piranesi worked in large part because of this metatextual narrative. Even without the quarantine context, much of the emotional resonance should still work. And this is, in large part, due to the narrative structure and epistolary format.

It’s no secret that I’m an epistolary junkie. In lighter epistolary novels, there’s an additional layer of novelty associated with getting to read really great gossip, a thrill associated with seeing “private” messages. In Piranesi, Clarke masterfully uses the epistolary format to create a tense atmosphere via dramatic irony.

It starts with Piranesi’s voice. Clarke’s writing is sparse, formal, with Proper Nouns Capitalized as you might see from a child. And Piranesi doesn’t sound like a modern person. He labels years based on events and places based on their characteristics. He keeps track of Tides in a Table. These are clearly old-timey behaviors.

Yet from the start of the novel, Clarke drops hints that something is amiss. Why does this old-timey person know what plastic is? Why does the Other have a “shining device”? By the time Piranesi mentions that his earliest journals start in 2012, it’s clear both that something is up – and that he has no idea.

This sets us up for a whole book’s worth of dramatic irony. It’s horrible to know someone has forgotten core memories; more horrible to know they’ve led to breaches of trust; but the worst is hearing that person guilelessly express their faith in their betrayer. Piranesi is the last person to understand his own identity – and even we’re in on the secret. Who’s gonna tell him? Are you gonna tell him?

It’s a masterclass in subtext, and the impact comes straight from the epistolary format. Journals are private reflections – there’s no reason to lie. And because we know Piranesi is writing his truth, we can feel true horror at the reality of the situation.

How epistolaries drive empathy

This is the first book I’m reading for the Epistolary Challenge this year – and if I‘m being honest, I was a bit nervous that I wouldn’t have much to say. (After all, I just wrote a roundup of my favorite epistolary novels for the year.) But Piranesi gave me plenty to think about – both about the format and how we read.

Piranesi is a great novel because it’s well-written, with intriguing characters, complex themes, and a creative setting. Piranesi is a great epistolary novel because Clarke uses the format to share information with the reader that the narrator does not know, without having to write an extra word. Where many epistolary novels piece together documents from multiple sources to imply / highlight discrepancies, Clarke does it with simple descriptions.

That ability relies on our own capacity for critical thinking, for interrogating what we read and others tell us. On Goodreads, the reviewers who struggle most with this book tend to have similar complaints: “I didn’t like the writing style. It didn’t feel natural. The narrator can’t even remember things.” And – well – that’s the point. The writing is not supposed to feel natural – and that stiltedness is supposed to incite curiosity and empathy. A narrator with a faulty memory should invite sorrow, not irritation. Epistolary novels really push the skills of imagination and empathy.

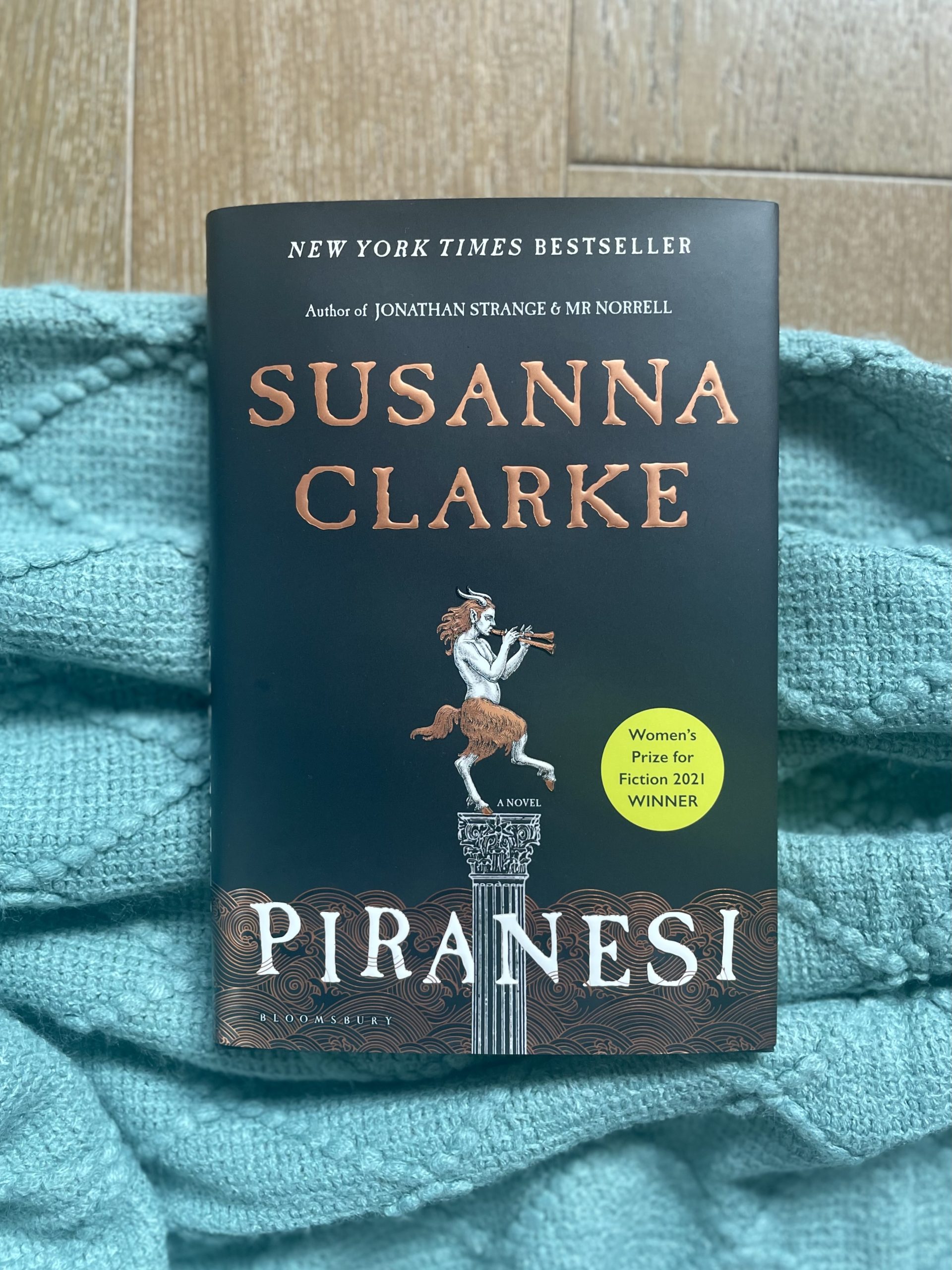

Piranesi was a weird, wonderful, and meditative read. I am so glad to have a physical copy and will likely come back to it. (Though not for the Epistolary Challenge again – that’s almost certainly cheating.) It’s got me hyped up for my next epistolary read – as soon as I decide what it is! (Any ideas?)

Until next time – stay cozy, and stay curious!