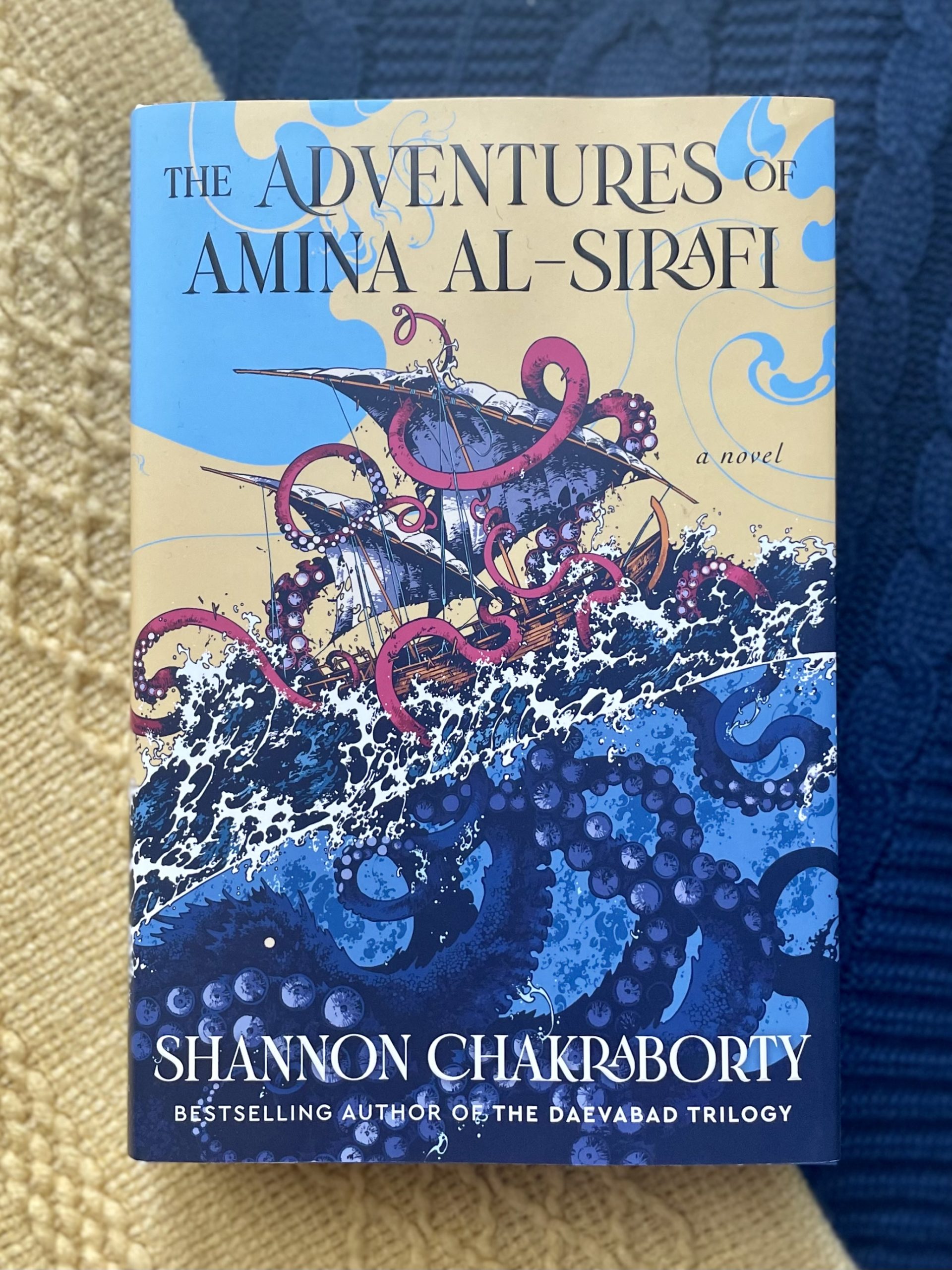

I’ve been reading a lot of mystery lately, so I was very excited to pick up a copy of The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi and really lose myself in fantasy for a while. Going into the book, I expected a story different from others I’m used to reading (I don’t read a lot of pirate stories, for example). And I got that in a lot of ways – The Adventures of Amina al-Sirafi is a fun, exciting adventure with an expansive world and mythology that’s under-explored in Western fiction. I love reading about historical trade routes in the Indian Ocean, and was pleasantly surprised to make it through the book without a single Roc.

But a week later (and perhaps it’s just the timing, with Mother’s Day just around the corner), I keep coming back to one element of Amina’s character: her motherhood. Chakraborty writes Amina as a different kind of mother than those I’m used to reading. Amina, a single mother, fiercely loves her daughter – but she also loves her adventurous way of life. Charkaborty portrays the tension between’s a mother’s love and a woman’s ambition in a way I’ve never seen before. And on this blog, “a way I’ve never seen before” means “a way I want to break down and understand more.”

The status quo of fictional mothers

Let’s start with my reference point. Most fictional moms that I read about fall into two categories: literary mothers and harried ones. Literary mothers focus on specific tales that we want to tell about motherhood. Mothers are heroines, struggling inside the patriarchy; mothers are goddesses, able to do 9 impossible things before breakfast. These fictional women perform some ideal version of womanhood before realizing that it makes them totally unhappy. Typically, their resolution involves a divorce, a new love interest, and acceptance that life is full of imperfections.

It’s that story arc that sets them apart from the second type of fictional mother, the harried mom. These mothers aspire to the “starting” lives of literary mothers, but they already live in the chaos. But harried moms (who are more likely to live in genre fiction – cozy mysteries are a common setting) typically start with a feeling of loss and emptiness. Over the course of their stories, they gain a sense of empowerment and ambition through some kind of adventure. These moms learn that their personal goals are more important than performative womanhood. It’s not about coming to terms with chaos – it’s about seeing beyond it to achieve a fulfilled life.

What do these fictional mothers tell us about the status quo of motherhood? That society holds impossible standards for mothers – they’re glorified but idolized, but on an impossible-to-reach pedestal. The act of motherhood, in fact, can erase women’s personal ambitions entirely. To have both a child and personal ambitions is so difficult that it warrants hundreds or even thousands of pages of written exploration. And that there’s a need for women to remind themselves that imperfections are ok, that they can have rich interior lives. Mothers can be nurturers and martyrs – but motherhood require conflict and tension with personal ambition.

What makes Amina different?

Enter S.A. Chakraborty, writing Amina el-Sarafi. At first glance, she looks like a harried mom, one who’s set aside her personal dreams to raise her daughter. But Amina is a more nuanced version of that character, in a way that feels revolutionary. She had agency in her retirement, and when she’s cajoled back to her seafaring ways, she loves it. Her daughter is a driving force throughout the novel – but she’s got strong ties and connections to her crew as well, and they’re extremely important to her. You never get the sense that Amina forgot her love of the ocean, nor her ambition to explore. Unlike her harried counterparts, she’s opted into this life, knowing all that she’d give up.

At the same time, it’s clear that Amina’s motherhood has change her in ways that she appreciates. Her relationship with her daughter allows her to care for her crew in different ways. In fact, her empathy for the difficulties of parenthood draws her out of retirement – she’s finding a deceased colleague’s daughter. And when the two finally meet, it seems that Amina navigates the situation differently than she may have done in the past. Her crew notices, understands, and even appreciates the changes – at least most of them. All this – and it’s mostly delivered through plot details, rather than heavy-handed explanations.

So what does it take to write a new kind of fictional mother?

1. A clever choice of narration

Chakraborty’s first tool is her narration. The novel is framed as a transcription of Amina telling her own story, to a scribe and friend. Because it’s first person, and because it’s a memory, there’s an implicit assumption that Amina chooses what details to share. And because it’s first person, and a memory, we trust Amina’s perception of her own thoughts and motives.

It’s also structurally helpful that the novel has a historical setting, and that Amina’s journey requires physical separation from her daughter. There are no cell phone calls or FaceTimes to interrupt the adventure or Amina’s reflection on it. Instead, when a trinket or an acquaintance reminds Amina of home, it reflects that deeper connection of a parent and child.

2. Show, don’t tell

Amina tends to share her feelings as responses to the moment – “it felt so good to be on the water” once she’s there, not “I had been longing to sail again for years”. As a character, Amina makes an analysis, chooses a path, and sticks to it, until something pushes her way. Details are shared as they happen, without deep exploration.

This means that readers can understand her character and values through those decisions. If Amina chooses to include or exclude someone for their safety of comfort, that’s an indication she cares about them – without requiring explicit exposition. She’s on this whole journey for her daughter, but that doesn’t mean her daughter factors into every choice. It’s a big contrast from modern harried moms, whose lives force constant thinking about their children.

3. Flashbacks for contrast

Chakraborty also uses flashbacks to great effect – we get to see single Amina in action. And this allows for both contrast with Amina as a mother, but also the throughline of her exploratory ambitions. It’s clear that Amina has changed since becoming a mother, and not just in word. She’s kinder, more understanding, pauses a little more before taking an action. And yet, the flashbacks illustrate that Amina has always dreamed big and acted quickly. Motherhood has expanded her identity and her worldview.

To be clear, I don’t think there’s one formula for this. The net result of all these writing choices is a story that treats motherhood and ambition as complements, not tradeoffs in a mother’s identity. Amina is a fierce, fascinating heroine, and I’d love to read more of her. And I hope we get more swashbuckling mothers, from their own perspective.

More literary adventures to come – but until then, stay cozy, and stay curious!