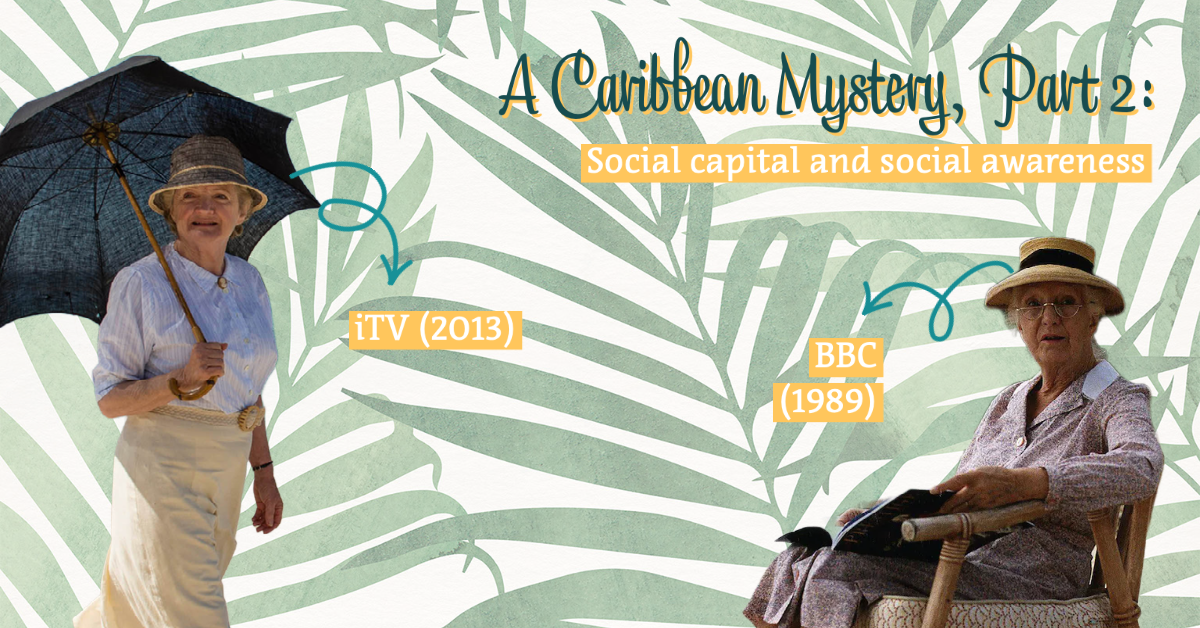

Summer in the Bay Area is cold and foggy – I literally walk to work in a puffer jacket. And so I’ve been looking forward to escaping into the BBC (1989) and iTV (2013) adaptations of A Caribbean Mystery. Who could fault hours and hours of palm trees and ocean vistas?

Well… maybe me, as it turns out. It’s not the beaches, but the content on them. A Caribbean Mystery places Miss Marple uniquely outside her comfort zone, and allows us to watch her build a network from scratch. But our adapters mess with this formula, and decide to add a little local color to the mix. Suffice it to say that results are mixed – with some good writing lessons as a result.

Miss Marple, alone?

In the last post, I highlighted one of the more unique elements of A Caribbean Mystery: Miss Marple is as alone as we’ve ever seen her. She’s on the island for her health, and knows none of her fellow tourists. Not only that, she lacks her more official network and connections – there’s no Sir Henry or DI Craddock to co-sign her deductions.

This means that, in the novel, we get to see Miss Marple work around official channels – as the police don’t know her. In doing so, she has to use an innovative mix of tactics: misinformation, gossip, and networking. We’ve seen Miss Marple incorporate each before, but this feels like the first time she’s code-switched to quite this extent. In my reading, the tactical flexibility highlighted her human expertise – this is someone who has agency in finding information.

It’s interesting, then, to see what happens in the transition to the small screen. The first change happens almost by necessity – there’s a consolidation of characters. In the novel, Miss Marple gathers information and inspiration from at least 10-12 other guests, but that’s hard to follow in a short TV episode. So we see characters combined, with the Canon, his sister, and Señora de Caspearo on the chopping block. We also see that Miss Marple has readier supporters in Rafiel and the police force than in the novels, particularly in the BBC version. These changes combine to paint a slightly different detective than the novel version.

Miss Prescott and the importance of gossip

Let’s first discuss the cut that both adaptation teams make – Miss Prescott, Canon Prescott’s sister. On the one hand, it makes some logical sense. There’s no gossip she can deliver that other characters can’t. But losing Miss Prescott changes our understanding of Miss Marple, because Miss Prescott highlights the Victorian sides to our heroine.

Take first the logical perspective: what happens when Miss Prescott’s information is delivered by other characters? When Esther or Evelyn or even Molly herself gives Miss Marple backstory, it’s a little less trustworthy. Each of these alternative sources has skin in the game, and incentives to lie. Miss Marple, then, is clever for using Miss Prescott to triangulate her facts – not just gather them. Cutting Miss Prescott rids us of this insight into her process.

It’s not only that, however. At many moments, Miss Marple and Miss Prescott have remarkably similar reactions to information or inputs. It’s these times that highlight Miss Marple as the Victorian Lady, not just Miss Marple the sleuth. Whether it’s their joint outward deference to the Canon or their mutual agreement to gossip anyways, these two characters’ similarities offer insight into how they learned to navigate the world. We can better understand where Miss Marple learned her tricks – and what sets her apart.

Growing a support network

One of those differentiating factors is her ability to earn the trust of skeptical, “logical” men. In the novel, Miss Marple understands that the local police may not trust her, and so she develops workarounds. First, she uses Dr. Graham to highlight discrepancies to the investigation. And later, she earns Mr. Rafiel’s respect with her logical thinking and confidence. In both instances, she plays to each man’s preferences, shifting her image to gain the influence she needs.

The BBC adaptation team, however, will have none of this. In their version of the story, the local police have not only heard of Miss Marple – she’s a police celebrity. As a result, they’re much more inclined to take her inputs than their novel counterparts. That also means Miss Marple needs to resort to less social jiggering to actually solve the crime – less of her mental energy is spent on persuasion.

But because the adaptation team is still stuck with the clues and the mystery in the novel, that just means the story gets simpler. Miss Marple is no longer a master in both mystery-solving and social manipulation. Contrast this to the iTV story, where she has to earn Mr. Rafiel’s respect (and engage with Jackson, who’s ignored by everyone else). Personally, I prefer the more skilled Miss Marple to the celebrity.

Local flavor

Neither adaptation team could resist the temptation to explore the local culture, with varying success. (Spoilers ahead!) In many ways, it’s an honorable impulse. Victoria’s death is perhaps under-explored in the novel, treated as mere mechanics instead of human impact. The adaptation teams attempt to right this wrong in two ways – they expand Victoria’s presence, and explore the local culture.

Focus on the people

Take first the different approaches to Victoria. The BBC has her literally invite Miss Marple to her village, out of sympathy for a lonely old guest. While this serves to humanize Victoria, I found myself skeptical that Miss Marple, a generally suspicious person, would be quite so open to a field trip. It’s a sweet scene, and attempts to carry the idea that “people are people the world over”. Yet the team undercuts this immediately by adding local superstition to the story, suggesting supernatural vengeance via Ninth Night.

The iTV team takes a lighter-weight approach, and it works reasonably well. Miss Marple is as friendly with Victoria as she’s been with any other servant, and Victoria is generally pleasant and kind in every scene. The tea expands her screen time and make sure she’s more than just a smiling servant. They also continue to portray her human impact via Errol, who clearly mourns her loss. Instead of trying to jam in the story of Angelic Victoria, they remind us that death has reaching human impacts. To me, this subtler approach works better.

Cultural …mishmash

Unfortunately, neither adaptation team sticks the landing on the local culture. Both incorporate local superstition in a way that makes this modern viewer wish for a cultural advisor or two. The climax of the story happens on a stormy night, and the BBC team decided to up the drama with some superstitious yelling once the culprit is apprehended. And the iTV team is no better, with their almost fetishized portrayals of vodou throughout the adaptation.

The intent here is admirable. But the execution is lacking, and in some ways, we get the worst of both worlds. Christie’s original novel may have lacked the local color – but the resulting storytelling highlighted the culprit’s greed and amorality. Here, the reduced attention on the mystery means we lose focus that theme, with only faux cultural appreciation to take its place. Aspiring writers, take note – cultural exploration can add – but only when it’s well-integrated with the themes, not simply sprinkled on afterwards.

—

This has been a bit of an unusual adaption exploration, but I found it more interesting to dive into these writing themes. What do y’all think of this format compared to the more strictly divided posts of the past? Let me know so I can shape the posts for At Bertram’s Hotel and beyond!

Until then, stay cozy, and stay curious!

2 responses to “A Caribbean Mystery, Part 2: Social capital and social awareness”

Great review. I love that you compared the book with both film adaptations and think your observations were right on point. I only just discovered your blog so haven’t read your other styles yet, but I very much enjoyed this one.

Thank you! Really appreciate you sharing and hope you get the chance to look around 🙂