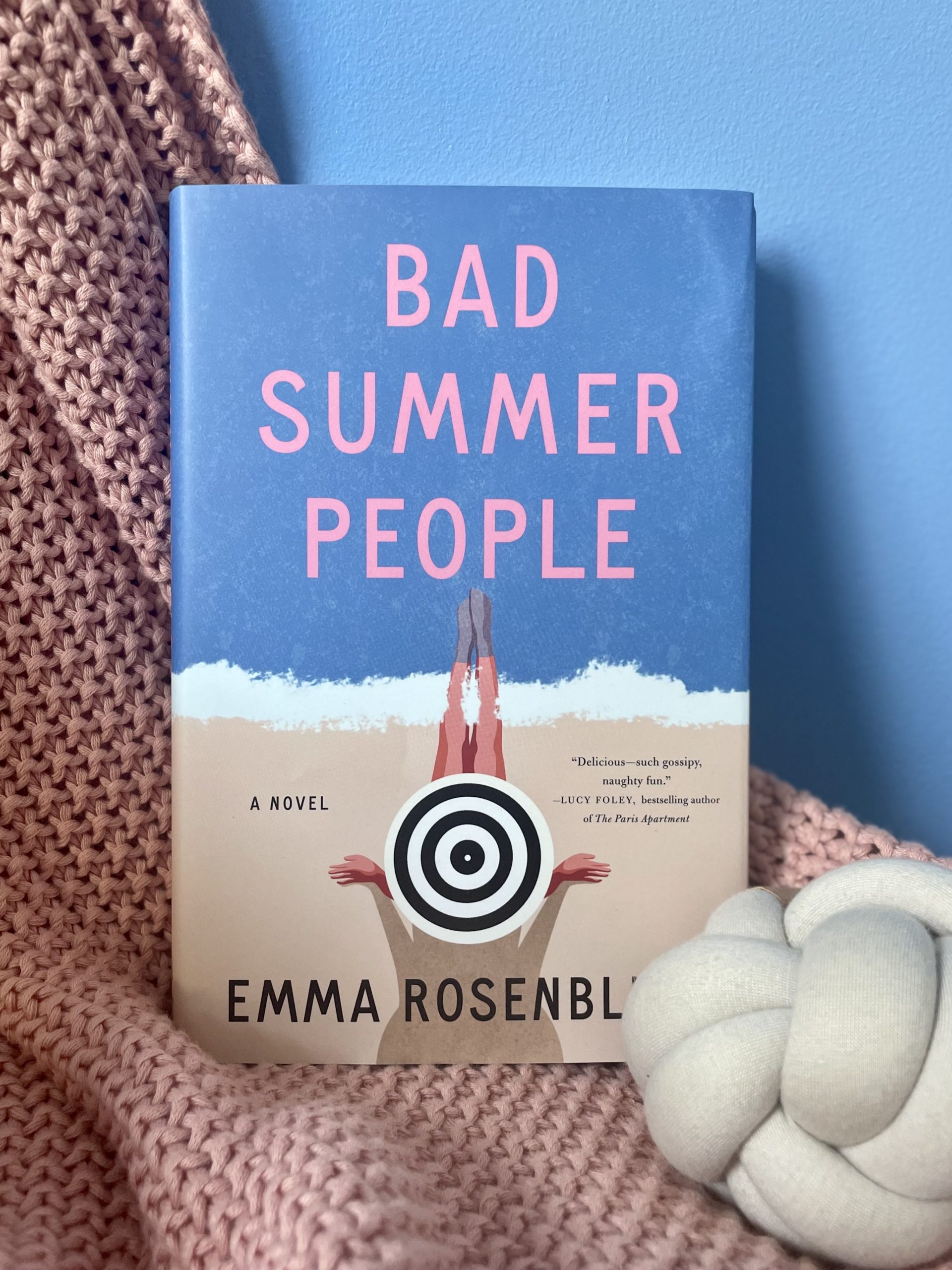

I’m back! Sorry for the long hiatus – I was in the midst of training and all of my fiction reading turned into case materials. But after a month of deep-diving into business problems, we are BACK with room to think more deeply about literary ones. And first on the list is Bad Summer People by Emma Rosenblum.

Setting the scene

Bad Summer People follows a group of unhappy rich folks as they summer on Fire Island. We first meet Lauren Parker and her husband Jason as they prepare for their summer. Jason grew up summering at Fire Island, and the Parkers return every year for tennis and traditions. Salcombe, the town they live in, is a tight-knit community – and as we meet more residents, we get the sense it may not be a very pleasant one. The Parkers, their friends the Weinsteins, and every one of their neighbors has some deep secret to hide.

Rosenblum makes sure we know this from the start of the book, which opens with the discovery of a body. Her talent for description is clear from these earliest pages. Whether it’s 8-year-old Danny Leavitt’s intentions in an early morning bike ride (he’s hunting for storm-uncovered snails), or his reaction to the dead body, Rosenblum uses details to paint a vivid, visceral portrait of events. Those detailed descriptions carry through the rest of the book, bringing summer on Fire Island to life. In many ways, the experience of reading Bad Summer People is the experience of the American Summer Dream. There are tennis tournaments and Fourth of July picnics and moonlit beach walks. I’m not much of a visual reader, but even I found myself picturing the sun and surf and sand of the island.

What makes a Summer Person bad?

And it’s those same details that make Rosenblum’s characters so intriguing. Her chapters switch from character to character, bringing each to life. We learn about Lauren’s anxieties and Jason’s fears. We learn about decades-old history in Salcombe and watch echoes ripple through to the present, each step a seeming inevitability. Rosenblum is excellent at writing tragedy – at telling stories of pain that seems so easily avoidable if only the characters could just be different people. Each detail she includes adds a layer of entangled complexity that makes each mistake seem like the only possible outcome. And her writing is kaleidoscopic, reflecting each scene back from a multitude of vistas to highlight differences between perspective characters. It’s like reading Greek tragedy with swimsuits instead of togas.

So what makes a Bad Summer Person? At the beginning of the novel, each of the characters struggles with a sense of things untried, goals unrealized. Whether it’s a decades-old unrequited crush or a work emergency that threatens a family’s livelihood, everyone has a goal to hide. To be clear, these are secrets of vanity, or fear, or desire – there’s no nobility here. They’re secrets that fail to accept real-world constraints, hidden hopes harbored at the expense of real happiness.

The tension of balancing these hidden goals with external perceptions drives characters to Behave Badly indeed. Only once those secrets are spoken aloud that the cast can move forward. A Bad Summer Person, in other words, is one that’s lying to everyone. And the resolution of a Bad Summer isn’t a good life, but a normal one – one with convention and compromises and constraints.

To judge or not to judge?

Rosenblum grounds her approach to a riveting, gossip-fest of a story with a journalistic tone. She’s not judging, she’s just telling every story as the character sees it. Any ugliness, any frustration you may feel reflects your morality as a reader, and your morality alone…

Or does it? Creating these characters in a way that makes their worst actions believable means that Rosenblum takes a uniformly acrid tone across all her narration. These are characters unafraid to voice their thoughts, even those that would normally stay subconscious. Many of the actions that might reflect positively – particularly those with a family / child orientation – remain unexplored.

But judgement is about more than tone. Certainly Rosenblum judges less than others authors might… But she routinely shares the worst in each character without any attempt to share the best. After all, stories only work by evoking an emotional reaction. If this were a truly morality-free zone, the transition of the book from summer spitefulness to deadly discoveries wouldn’t matter. But the death is not merely an escalation of the nonsense that’s come before it; Rosenblum actually goes out of her way to humanize the victim shortly before the end. She wants your investment – not just your interest – and that requires judgement, not just observation.

Funnily enough, it’s that judgement that made the book a bit exhausting in the end. I started out loving the characters, the drama, the gossip, but found myself wishing to see their humanity. By the end of the novel, I found myself exhausted and glad to turn the last page. That might mean Rosenblum did her job – because this is exactly how I’d react to these people in real life. Maybe it’s just that this is the year of billionaires acting up, or that the rich have it so very very good, but it’s hard to muster continued enthusiasm for this kind of intrigue…

…which is, of course, why I have a whole lineup prepared of books about rich people, behaving badly. Even our July Miss Marple lines up – we’re gonna read A Caribbean Mystery which is a true resort read. I’m very excited to share these with you – and would love to get your recommendations for others to add to the list!

Until then – stay cozy, and stay curious!