As we’ve read through Christmas mysteries this week, things have stayed on the reasonably light-hearted side. (At least, as light-hearted as you could expect with murder in the mix). Because house parties often involve friends and family, the genre is a great way to explore family tension. most of these stories limit their suspect pool to the inner circle – that’s what makes them timeless. After all, a complex family dynamic is a tale as old as time.

Our read for today does not meet those criteria. An English Murder by Cyril Hare is firmly set in its time and place – England, in the early 1950s. Hare writes with deep cynicism about English society: the book is a thinly-veiled criticism of inheritance laws at the time. (Hare was a practicing lawyer, with Very Strong Opinions.) The cast includes a Czech caricature and a deeply-antisemitic noble, who would not pass the publishing bar today. If you choose to read this – read it more like a historical artifact, and less like any other murder mystery.

(Content warning: The novel features an anti-Semitic character as an object of ridicule. This review therefore contains references to his behavior – nothing descriptive, but be warned!)

An investigation into the English upper-crust

An English Murder starts off from the perspective of Dr. Wenceslaus Bottwink, Ph.D., in a cold tower, pursuing historical research. Unlike many country house mysteries, it’s clear that Dr. Bottwink is a second-class citizen in Warbeck Hall. He’s not truly welcome with the English upper crust, but not a servant, either. Bottwink is smart, observant and resilient – in fact, he’s a concentration camp survivor.

As Christmas approaches, Lord Warbeck’s family descends upon the family estate, each as unlikable as the last. The cast includes: a powerful cousin with a particular sense of entitlement; an ambitious political wife, who detests said cousin; a niece who hopes to marry Warbeck the Younger; and Warbeck the Younger, a raging anti-semite and entitled prick. They’re supported by the house staff, including the family butler and his daughter, a pregnant “widow”, and the cousin’s security staff. There’s a ton of tension to unpack – and when a murder occurs at the stroke of midnight, they must solve the mystery to avoid a scandal.

Bottwink serves as Hare’s eyepiece into upper English society, and his view is unsettling. His mere presence brings out the worst in the younger Warbeck, who goes out of his way to be as aggressively anti-Semitic as possible. (Reader note: this is really distasteful. See earlier note about reading this book as a historical artifact, not a fun mystery novel.) His innocent questions of clarification force each member of the cast to explain uncomfortable truths. His limbo status between “upstairs” and “downstairs” enables him to see the full household dynamics, including the full mess of English inheritance law. And when Bottwink eventually solves the mystery, the only truly clear-eyed member of the household, Hare demonstrates the folly of the English attitude towards middle European immigrants.

Satire for Christmas

It’s a sharp message, and Hare hammers home the themes of class and immigration injustice again and again. Unlike other Golden Age authors, who stick solely with the upper-class householders, Hare consistently centers the “downstairs” perspectives of the butler and his daughter. He also emphasizes the tricky role of the security officer, who serves as both investigator and protector for the Parliamentary cousin.

Hare has little patience for the sentimentality and nostalgia for the “traditional English way.” In the opening scenes of the novel, Lord Warbeck looks over his run-down estate, made pristine by the snow. Yet it’s only when the rains come and reveal the true nature of Warbeck Hall that the truth is revealed. And that truth favors the “downstairs” people of the book – ready, at last, to take their place in the world.

It’s a dramatically different take on the Christmas mystery, and in many ways it’s before its time. A diverse protagonist and a clear working-class sensibility make Hare’s novel the most political of all the books we’ll review this week. The themes are resonant today – but the presentation might make you squirm.

An interesting historical artifact

I really enjoyed An English Murder – but as a historical artifact, not as a Christmas murder mystery. It was a great reminder of how mysteries deliver so much more than “just” a puzzle. Hare’s snark made me laugh out loud at moments, and I appreciated the progressive perspective on the Golden Age mystery genre.

That said, I would not recommend this to everyone – it definitely contains sensitive topics, and while the anti-Semite is the butt of the joke, he’s still very openly anti-Semitic. (Given the current tenor of political discourse, this doesn’t feel as purely historical as it should – but it might still be a tough read for some.)

Read this if:

- You’re interested in a satirical mystery about 1950s England

- You’re intrigued by a Manor House mystery that takes the side of the “downstairs” folks

- You find the image of the Chancellor of the Exchequer getting stuck in a creek and dragged up by the collar as funny as I do

Skip this if:

- You don’t want to read anything with an anti-Semitic character in it, even if he’s the butt of the joke

- You’re looking for a cozy Christmas mystery

- You’re looking for an apolitical read

Random reading notes:

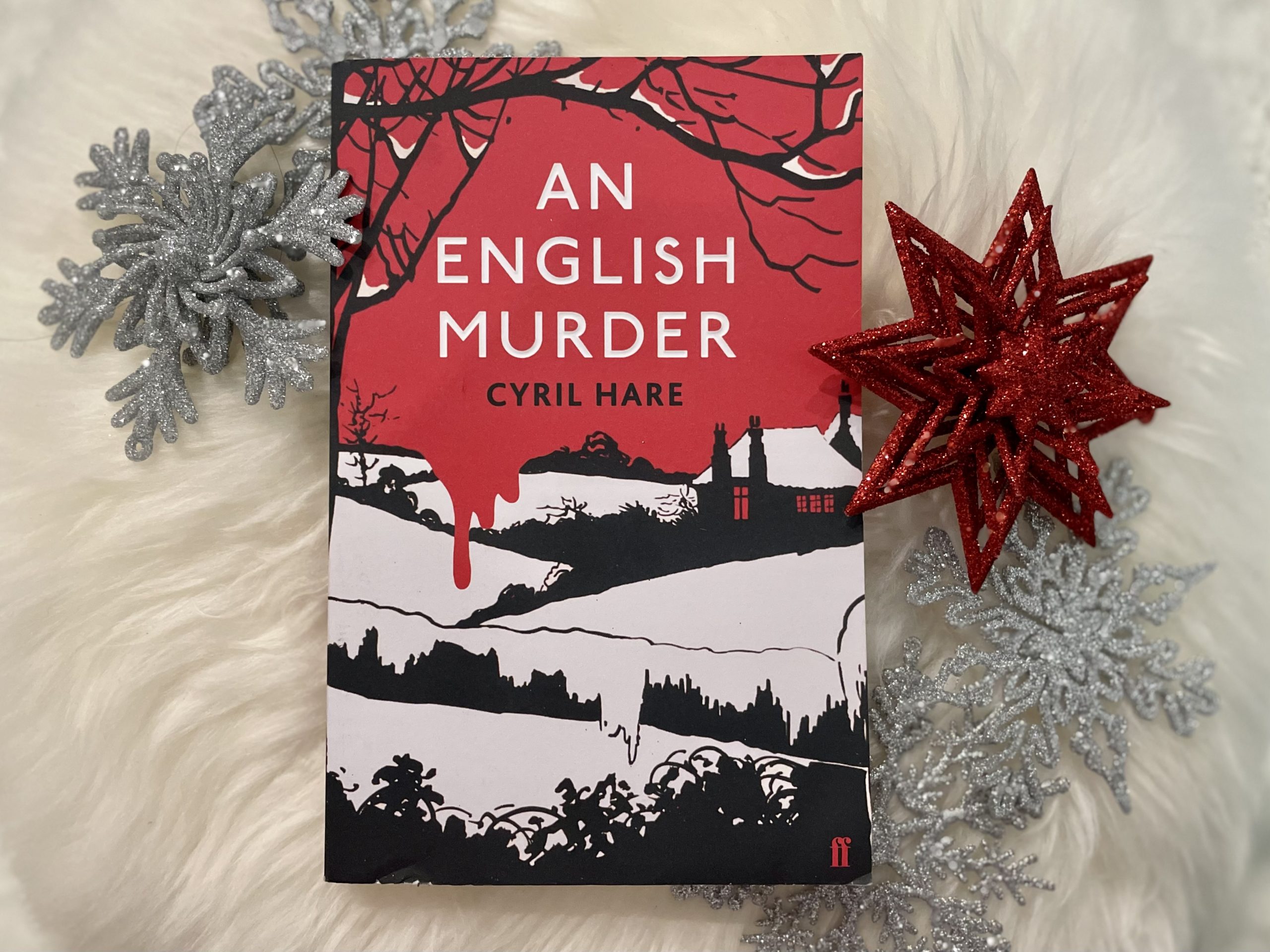

- I almost didn’t read this! It was a last-minute add (and kind of just for the cover). A good reminder to let myself be surprised…

- This made me want to read more satire in 2023. Any recommendations?