November is Native American Heritage Month, and I want to share one of my favorite annual traditions with you to celebrate. A few years ago, I helped run a local diversity-themed book club, and we hit the month of November. Various other members suggested a variety of reads – some wanted to read the new Melinda Gates books; others wanted more practical tips on diversity issues – when I realized that the San Francisco public library was having a read-along of There There by Tommy Orange. Spurred on by the promise of low-effort programming (and free book access), I suggested we read the novel to recognize Native American Heritage Month.

I was not expecting my own reaction to the book – nor the amazing discussion we had in response to the subject matter. My book club, all reasonably “woke” people, turned out to be shockingly under aware of the issues facing Native people in the US today. I’ve since stepped away from the book club – I participate, but don’t choose our content – but since that year, I make sure to stop and read something by a Native author every November. And this year, I want to share some of my favorite picks for your November reading list.

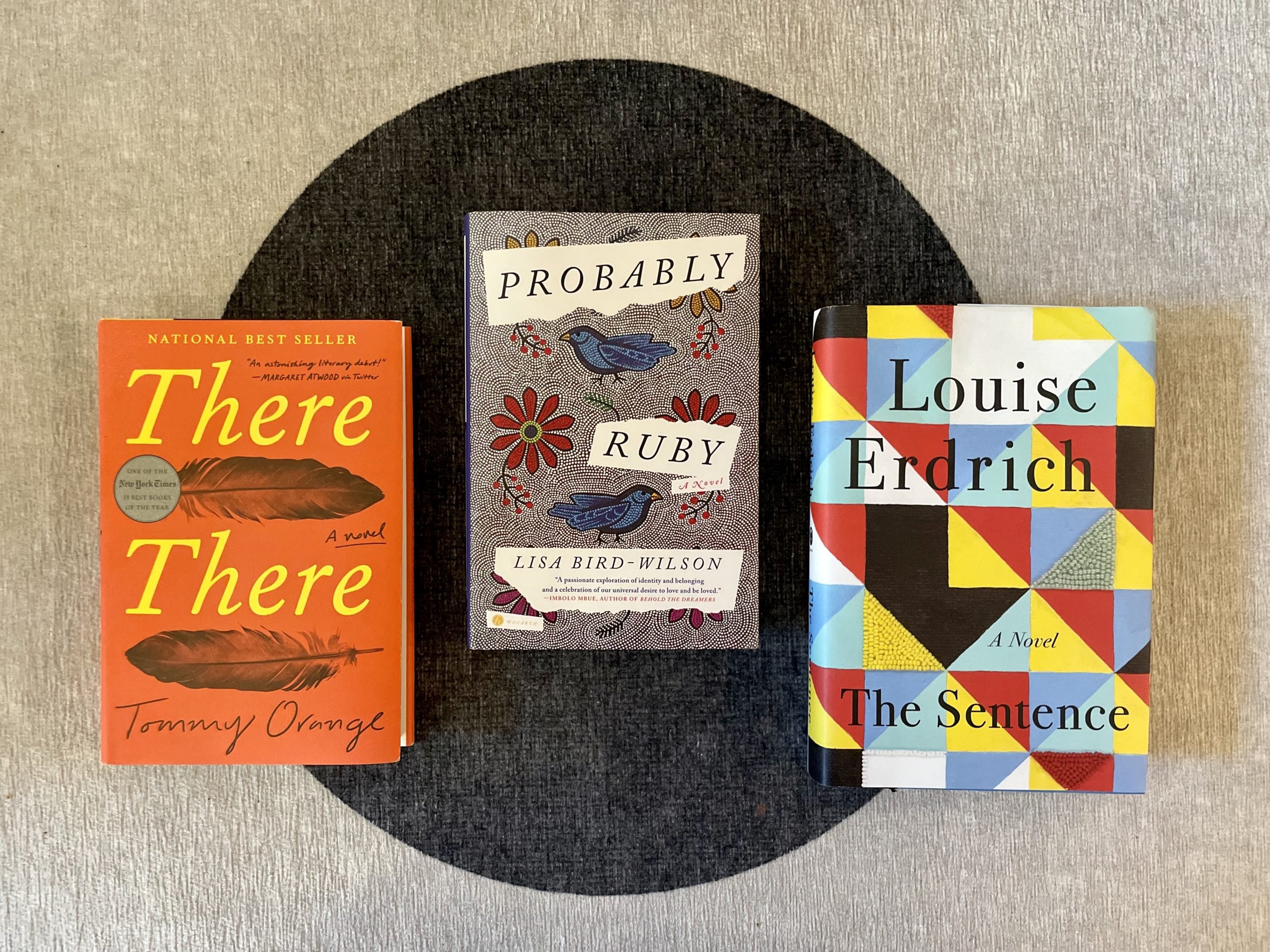

Pick #1: There There by Tommy Orange

We have to start with the original, There There. This book left me devastated and it took my breath away. It shares the stories of a dozen or so perspective characters, each Indians with some ties to Oakland, as they converge on a big powwow. It explores the reality of modern Urban Indian life, as well as the historical Occupation of Alcatraz (both of which I was profoundly ignorant of until reading this book).

At first, it’s kind of fun trying to tie the different narratives and timelines to each other. This gives way to profound dramatic irony and tension as the stories converge and crescendo towards a reckoning. I won’t spoil the story, but suffice it to say the climax left me amazed at how much I cared about this hodgepodge of characters.

Orange is a skillful character writer and lays out a ton of exposition for readers like me who may not know much about modern Native life. Besides the impactful ending, I was left with a sense of sorrow and isolation for the characters’ loss of identity – stolen by various government and social systems that force them to integrate. Traveling cross-country to reach a powwow reminded me of the many cultural gatherings created by diasporic groups (I grew up attending such a conference for Bengalis) in attempt to keep the culture alive. The poignant writing and hard-hitting ending make this my top recommendation for this month.

Pick #2: Probably Ruby by Lisa Bird-Wilson

Continuing with the theme of identity, next on our list is Probably Ruby by Lisa Bird-Wison. Probably, Ruby shares a similar pastiche-like structure to There There, compiling a series of moments in the lives of various Native characters. These characters are tied together by their relationships to the protagonist, Ruby, who features centrally in about half the vignettes.

Ruby is part-Métis, part-Cree, and fully adopted. Adults around her treat her Native heritage as something to hide from the moment of her birth, and she struggles to create a sense of self. The chapters bounce back and forth between past and present: Ruby’s struggles, from childhood to the modern day, are interspersed with the stories of her family – her grandparents, who attended Residential schools; her father, who died young, and her mother, who was forced to give her up in shame. The juxtaposition emphasizes the pain and loss associated with each generation.

Ruby’s stories, and those of her family members, encompass a sense of longing for identity and community. The book reads like an elegy for way of life forever lost – for people ripped from their roots and forced to forge on. Where There There shows community-level impacts, Probably Ruby focuses on the personal, intergenerational hurt felt by First Nation members today. This one takes some time to process fully, and it’s time well-spent.

Pick #3: The Sentence by Louise Erdrich

This last pick is a book for our time, and a particular highlight for book lovers. It’s a little different than the other two, which are primarily concerned with Native identity. In The Sentence, Louise Erdrich both explores themes of Native identity and reflects and refracts the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Her protagonist, Tookie, finds the bookstore she works in haunted by the ghost of a customer. As she tries to navigate the dual challenges of a haunting and pandemic (and all the social upheaval that followed), Tookie faces her identity as an ex-felon, a mother, and an Indian.

Unlike the other two novels, The Sentence is written in first-person and, for the most part, as a linear narrative. There are enough plot threads in Tookie’s life – the ghost, the general social upheaval of the pandemic, various bookstore and family happenings – to make the story complex. The constant thread of Flora’s ghost – and Tookie’s identity – tied together these different narratives of a woman learning to be at peace with herself.

Reading this book transported me back to the mental space the early pandemic, those days where we were shut in as the world broke down around us. There was sense of reinvention and forced self-discovery in those days that made the themes of identity more tangible and relatable. The dramatic irony also made for an interesting reading experience as I found myself bracing for events that I knew had to come. This one hits close to home, and I highly recommend it as a more personal, contemplative read.

Identity, refracted

I cannot pretend that these books give full insight into the many different ways to be Native American. But for me, they’ve offered an entry point into a world I was sadly ignorant of – modern Indian life.

Growing up in Florida, we learned bits and pieces of Native American history: how the Seminole and the Miccosukee were chased into Florida and got so good at hiding in the Everglades that the government gave up, tidbits of culture taught to us in stories and refracted through the lens of white writers. I remember vaguely the scenes of environmental doom and animal adventure in The Talking Earth by Jean Craighead George, which featured a Seminole protagonist and probably contributed to my romantic sense that most Native people live out in nature or reservations. As I grew up, I knew from news stories that things were not quite so simple – but I never took the time to find out just how complex.

So reading these stories, of Native American people in cities and in lives like mine, opened my eyes. And reading their stories of identity struck a particular chord. As the child of immigrants, I find many of the questions these protagonists face extremely relatable: How do you learn and respect your family history, while forging ahead to make a new path? How do you find those who understand your story and identity, and why is it important to do so? How can you honor your cultural roots when you never got to steep deeply in them, when you feel like an impostor? And for me, it’s important that these questions are finally coming from Native voices – that these authors can share a multitude of experiences and interests and concerns.

So this November, I hope you pick up one of these reads – or, if you’ve already done so, another book by an Indigenous author – and take a moment to reflect. And then, if you want to make a difference, please consider donating to one of the many nonprofit organizations set up to benefit Native Americans. ( I donate to the Association of American Indian Affairs, but here’s a great list of potential other options.) And no matter what you do – stay cozy, and stay curious!